This is the age of many new and not many welcome things. Yet the incredible availability of data should now be able to tell us far more about COVID19 and what this means for us. In particular, its comparison to pandemic flu, which is sometimes touted in cyberspace and in politics.

So let’s look back and see how many people have been infected and what happened to them?

What are the overall chances of dying from COVID19?

Public Health Englands latest tally is perhaps the place to start. As of the 3rd June there has been a total of 217,076 cases and 35,456 deaths. The case fatality rate is thus 1.6%, but this of course misses all those people out there who don’t get tested due to mild or absent symptoms, or because they don’t want to or can’t get tested.

Based on this, the overall mortality in the population varies from 30 to 70 people per 100,000 people. In Devon with our wonderful ‘peripherality’ our chance, so far, of dying from COVID19 has been 0.03%, rising to 0.078 in the current hot spots in the North.

Put another way, 99.93% of people in Devon have survived thus far. However this is not to minimise the pandemic or its effects, the average death rate of 50 deaths per 100,000 people adds up to a 32,000 deaths across the UK.

What happens to people who do get infected?

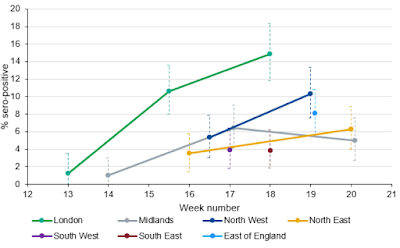

Information from Public Health England offers an idea how many people in the community have come across COVID19 in terms of developing antibodies. The tests were done on blood donors to give a sort of baseline of the number of people in the community who have been infected.

Of course we assume the test are reliable. Like anything else, they are far from perfect. Yet they are more likely to be accurate in this sample of blood donors who would not have been having active symptoms at the time of sampling. People seeking tests for symptoms might not have generated the antibodies the tests measure.

So this represents the best measure of background level we have right now.

|

| UK Prevalence of COVID19 |

Results vary across the county, but my previous guesstimate of about 2% in the South West turns out not to be far off the 4% these figures reveal.

Put another way, 96% of us down here in the South West have not come across the infection and nor have 86% of Londoners.

With such an infections disease, this is rather a surprise. Either the restrictions have been very successful, or there is more to COVID19 immunity than meets the eye. I think there is but that’s another story.

So, lets get the back of the envelope out:

The figures show that about 8% of people have developed immunity to the virus. For a UK population that represents about 5 million people.

With 60,000 hospital admissions that means that your chance of being hospitalised with your COVID12 infection is about 1.2%

The study below shows the overall hospital mortality from COVID is 26%.

So the overall mortality so far for anyone infected is 0.3%, or just less than one in 300.

What happens to those admitted to hospital?

It is reassuring to know that for the majority of people COVID infection will not be a problem.

However for those with more severe symptoms hospital admission is necessary and this has so far been the case for about 60,000 people in the UK with peaks over March and April, declining slowly since.

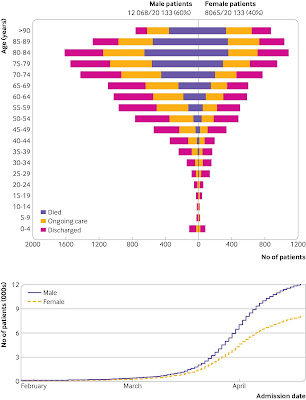

A paper from the “International Severe Adult Respiratory and Emerging Infection Consortium” otherwise know as ISARIC detailed what happened to over 20,000 hospital admissions to UK hospitals since the onset of the pandemic. This represents about 35% of the total 60,000 COVID-19 admissions in the UK in between 6th February and 19th April, when cases were increasing rapidly.

In words and graphs, this is what they found.

Overall:

- The average age of patient admitted was 73 years.

- 60% of admissions were men.

- The median age of those dying was 80. (for every case over 80 there was one below)

- The average age of the 17% of people needing mechanical ventilation was 61

For patients not needing admission to intensive care:

- 47% were discharged

- 27% were still receiving care

- 26% died

For the 17% transferred to critical or intensive care:

- 28% had been discharged

- 41% were still receiving care

- 32% died.

Other illnesses in those hospitalised were:

- Chronic cardiac disease – 30.9%

- Diabetes – 20.7%

- Chronic pulmonary disease – 17.7%

- Chronic kidney disease – 16.2%

- Asthma 14.5%

- No other illness – 22.5%

In some ways, COVID19 is doing just what would be expected, hitting the most vulnerable the hardest. Nonetheless nearly one in 5 admissions were of previously fit people.

I hope that the hospital mortality will come down with time as the pandemic enters a calmer phase and management and treatment improves.

So how does this compare to flu?

I keep hearing that this the pandemic is not any worse than flu (think Trump and Bolsonaro). How true is this? Over the last 5 years average deaths in England from flu, reported by PHE run at 17,000 a year with a peak of 28,000 in 2014/15 and a low of 1,700 in 2018/19.

In that sense it COVID19 is already 3.5 times worse that Flu in terms of deaths, and we are still surfing along long tail of the first wave.

Hospital data reveals that over this flu season there has been 1,815 admissions for complications related to flu which makes COVID19’s impact 33 times worse than flu.

We have been lucky with flu this year, but COVID19 problems are in addition to flu, not instead of it.

The comparison also fails when we consider our flu immunisation programme has conferred high levels of immunity in the at risk populations hit so hard by COVID19. Perhaps the present pandemic also sheds light on how well we have done to combat the dangers of flu, though new strains are being generated making the future unpredictable.

So flu pales in significance when compared to COVID19 and any comparison can be, um, put to bed. With painful irony, this particularly apples to Trump’s America and Bolsanaro’s Brazil.

Behind the numbers

From my point of view the hospital figures are make sobering reading. There have been many very sad scenarios played out for individuals and their families.

BAME groups and the underprivileged have been particularly hard hit both by the virus and the economic impact. The Black Lives Matter protests coincide increased recognition of the difficulties bestowed on people by the colour of ones skin and inherited poverty which have led to poor health outcomes due to COVID19.

The worthy noise of the protests is in sharp contrast to the deafening silence of the tobacco and sugar industries. Their terrible history of slavery, environmental destruction and their ongoing negative impact on health continues to be rewarded by extravagant global profits.

When I saw the statue of Coulson, that prolific slave trader, pulled down and dumped into the murky waters of Bristol harbour I saw a number of historic threads being puled together: slavery, sugar, obesity, diet, all encapsulated in that one moment.

Reasons to be cheerful?

Treatment

Things will get better. There is still lots of hope for the many antiviral treatments under evaluation despite some early disappointments with remdesivir and hydroxychloroquine. NHS staff have learned much about how to improve management of COVID19 patients and together with the hope for a vaccine, COVID is something we can live with. We will have to.

Better reactions

Understanding of the virus and its behaviour is getting better all the time. We have been very much behind the curve, but hopefully will do better next time. Experience lay behind the quick reactions of China and South Korea who had to deal with COVID19’s cousin SARS back in 2003, now we have no excuses.

Looking after care homes properly

With adequate supplies of equipment and constant testing, care homes could be kept COVID19 free. Many problems remain, particularly viability of homes affected by infection, fragmentation of the sector, patchy communication and the growing issue of underfunding.

Better and more local restrictions if at all

However slow our lockdown was, I cannot see any explanation for the low rates of death here in Devon other than restriction of movement. Indeed since its relaxation our R0 number has been creeping up, now standing at 1 as of early June. Local restrictions, if needed at all, can be tailored to reduce infectivity without the economic hits of blunderbuss national approaches.

Population Health is in the spotlight

The social determinants of health are critical in making pandemics better or worse. In this sense even hardened free-marketeers must see that we cannot afford current levels of poverty and that Austerity has cost farm more than it ever saved. This hard evidence provides impetus to integrate health and wellbeing more into political decisions.

The dramatic effect of pre-existing illnesses caused by smoking and diet is sobering too, yet this offers positive messages for how to stay well and avoid the many avoidable risk factors.

Staying well has never been more important

While we cant do anything about our age or the colour of our skin, there are lots of positive things we can do to reduce our risk of COVID19 as well as a host of other illnesses. Many people have taken positive action to improve their health.

As I reflect on of Coulson’s bronze sinking into the mud, I too hope for change. The connection between the horrors of slavery and its role in the production of sugar and tobacco are coming more into the public mind. The pernicious effects of these industries continue to manifest today as lung disease, obesity and diabetes which particularly hits the BAME community and are brought into sharp focus by COVID19.

Everything is linked.

Yes indeed, very much in the news at the moment. So it should be.

Thanks Colin – a very informative read, and the first I've read that links current poor health outcomes for our BAME fellow citizens with industries spawned by the abhorrent commercial practices of our slave-owner ancestors.