SUMMARY

- The third wave is receding in the UK and vaccination is significantly reducing hospital admissions, so this phase of the pandemic is over.

- We either go for Zero COVID, or accept that we have to live with the virus – it looks like we have chosen to live with it.

- This means Sars-Cov2 will not go away and like flu might become a seasonal infection needing regular vaccinations for those at risk.

- Suggestions that it will be ‘like flu’ means it might be helpful to look at Influenza, and its effect on history and humanity.

- This might help us think about how SARS-Cov2 might play out.

Introduction

Early in the pandemic, I listened carefully while sceptics inaccurately called Covid19 ‘just’ another flu. Like many COVID falsehoods, the statement is way off the mark, yet contains an grain of truth. Our experience with SarsCov2 has some resemblances to pandemic flu, so might it now evolve into something resembling seasonal flu?

Elimination of SarsCov2, termed Zero Covid, is potentially possible when low levels of community infection enables the proper isolation of cases and control of outbreaks together with quarantine for international travel. The virus would have nowhere to go. It seems hardly likely in the UK given our failed testing and tracing system, our reluctance to control international travel, our social inequalities, poverty, poor public health and crowded housing.

It is therefore no surprise that Matt Hancock is telling us he hopes that we will be able to live with Sars-Cov2 like we live with flu. That being the case, might the history of influenza give us some idea of where we are heading? I will leave that to you, but this is a scan through out relationship with influenza and what the parallels with COVID19 actually are.

Influenza’s beginnings

Flu is likely to have jumped from its long term co-habitation with waterbirds to humans as soon as we started herding animals and living in crowds – about 12,000 years ago. It is argued that the first major outbreak might have been 5,000 years ago in Uruk in what is now modern Iraq. Its 80,000 residents within a walled city with no immunity would have been hit hard.

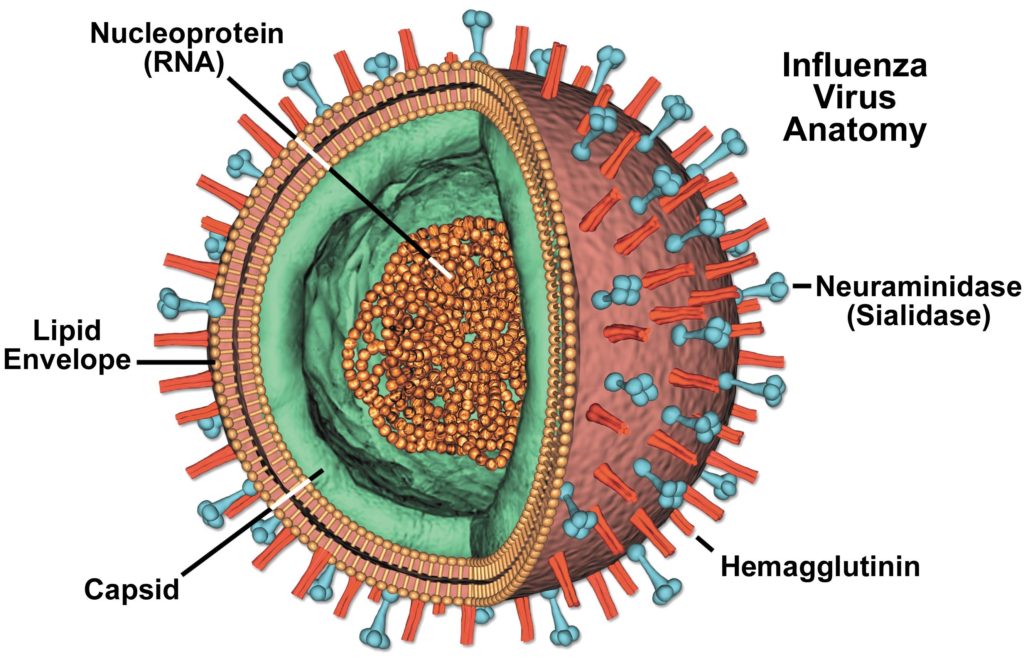

The flu virus – its genes are surrounded but a capsid then a fatty membrane with H proteins to get it into the cell, and N proteins to let it out.

The first written account was possibly the 412BC “Cough of Perinthus” described by Hippocrates in Greece, though this might have been due to diphtheria. Influenza went on to devastate the armies of Syracuse and Rome in 212BC and Charlamange’s armies in the 8th century AD. In 1557 it killed about 6% of English folk at the time of Queen Mary, far more than “Bloody Mary” managed to execute.

Influenza, together with smallpox and measles, contributed to the estimated 160 million deaths in the Americas following the arrival of the Conquistadors. Its rapid and devastating spread led to the whole continent being conquered with ease and was an early example of the impact of disease on human history. In exchange, it it likely the pre-Columbian Americans gave us syphilis which was a mild illness in the Americas.

The spread of flu similarly wiped out swathes of Antipodean Aborigines and inhabitants of the Pacific Islands, all caused by the arrival of infected but at least partially immune European Invaders. Its impact on history and the development of the modern world is undeniable.

Going global

The first global pandemic was in 1580, possibly starting in Asia, bringing with it a mortality of 10% in European cities. It was then the name Influenza was coined – it was thought to be under the ‘influence’ of the stars. What else would Astrologers think?

The Industrial revolution hastened in more pandemics; two in the 19th century, the later Russian Flu was the first to be followed, however loosely, by epidemiologists and was estimated to have killed 1,000,000 people in three waves. There were outbreaks in China too but they never seemed to go global in a world which was for the vast majority of people, a very local matter. Viruses need humans to spread to spread themselves.

Then came World War 1, which welcomed us to the new century and featured the sad mixture of some very sophisticated weaponry, new transport technology and some backward, primitive politics. It was also the first global super-spreader event. Though ignited by the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand the underlying cause were treaties between empires competing for the right to ransack the world.

Bad Medicine

Coupled with this was some very bad medicine. When Kaiser Wilhelm’s mother Victoria went into labour, she was knocked out with chloroform to enable a pain free labour foolishly deemed appropriate to royal dignity. Unfortunately, it also created a difficult birth for little Wilhelm who, in the absence of maternal effort, was extracted with forceps, suffering nerve damage to his left arm. (Erb’s palsy), leaving his arm permanently limp.

To make matters worse, various treatments, some of which verged on torture, were attempted under Royal pressure to cure his incurable palsy, which was again deemed incompatible with the myth of God given royal perfection. This, and his abysmal treatment by his mother, disfigured him mentally for life and his embittered attitude played a significant part in the origin of WW1, which in very good part led to the devastation of Spanish Flu. It was potentially decisive in the German defeat and also disabled the American president, whose attempts to moderation the worst of the Versailles Treaty whose stringencies paved the way for Fascism and World War 2.

Was this chloroform birth and its direct effects the most consequential medical accident ever? I can’t think of a worse one.

Spanish Flu

I digress. The new century and its war meant mass movement, mainly of young men, across continents and back again for the survivors. The sun never set on the British Empire at that time, and ‘volunteers’ were drafted in from its global corners to do the dirty work, including the Chinese Labour Force.

As with SarsCov2, this mass transport fuelled the global spread of flu. Ultimately the number of war losses, 14 million, were dwarfed by the 50-100 million variously estimated to have died from flu.

It says something important about our culture that there are a few small monuments to those felled by the pandemic, while those killed by the insanity of war are celebrated in cement and stone all over the world. Unlike Sars-Cov2, and like the war, most of the victims were younger people in the prime of their lives. In Asia and Africa, mortality was estimated to be 30 (yes thirty!) times the European losses.

At the time, with the identification of viruses some time away, it was considered by many to be due to one of the bacteria prominent in the secondary pneumonia which complicated flu.

A bacteria isolated by Richard Pfeiffer in a previous influenza pandemic in 1892 and thus called Pfeiffer’s Bacilli, (now known as Haemophilus Influenzae) was cultured from some patients but not others. Vaccines were made against this and used, but with limited success – though a part of secondary infection in the lungs, it was the wrong organism.

So flu went its own way and receded after the third wave in 1919/20. In its wake came many long term complications including widespread cases of post viral depression, a particularly aggressive form of Parkinson’s disease and long term neurological problems. There are echoes of this in Long Covid syndromes.

As it took the horrors of World War 2 to allow novelists to write about World War 1, it is only in the last couple of decades, with the ascendancy of modern virology and epidemiology that we are beginning to properly understand and write the history of that pandemic. It takes that long to be able to look back at what happened and why.

20th Century Flu

The descendants of the H1N1 strain that caused Spanish flu have come back on a seasonal basis and continued to cause problems through the century. There were more pandemics too: Asian flu, caused by the H2N2 sub-type (1957) caused 1 million deaths, Russian flu (1977 – H1N1) led to 700,000 deaths, Hong Kong flu (H3N2 -1968) took 800,000, Swine Flu (H1N1 – 2009) 400,000. So seasonal flu is a something we have learned to live with, and vaccination has reduced its impact. Intermittent pandemics are something we will always have to watch for, wait for and adapt to, pretty much in the same way we have managed COVID19.

The Big One

For some time virologists have been predicting the “Big One”. A combination of the lethality of bird flu with the transmissibility of swine flu. Or a novel virus like Hendra, Ebola, Nipah or others but with that deadly combination of virulence and transmissibility. To date this has not happened, but with chickens and pigs kept in large industrial units the conditions are ideal for mutations to occur and spread. No, I’m afraid Covid19 is not the “Big One“. That will be a more deadly virus with mortality rates far higher that Sars-Cov-2 or most of the flu pandemics we have seen over the century.

Covid and influenza

Rather like Sars-Cov2, most flu victims recovered, but unlike COVID19, Spanish Flu tragically hit the 20-40 age group and the very young as well as the elderly. At the end of the pandemic, there were millions of widows, widowers and orphans. Thankfully, this is not the case with Sars-Cov2.

When I saw the terrible stats come in from China and Italy last March, beyond the anxiety of what was to come, I felt relief bordering on joy, that the younger generations seemed spared from the worst it had to offer.

There are similarities in that they both cause pneumonia, gum up the lungs, cause a deep cyanosis when the skin become blue due to lack of oxygen and lead the a dangerous and often deadly cytokine storm when our own immune reaction to the invader causes overwhelming inflammation. They both cause long term complications and can be mitigated by reducing spread in similar ways.

There are also big differences between the pandemics defined not only by the virus but also by the development of modern medicine. Hospital treatment and support has saved millions of people across the world from the worst of Sars-Cov2. It is hard to know how many people have been hospitalised globally, but here in the UK it is quite reasonable to assume that most of the 423,000 patients hospitalised would have perished without modern technology, treatment and intensive care. Perhaps Neil Fergusons prediction of 500,000 potential deaths was not so far off the mark – without medical help mortality might well have been this high.

Then there is vaccination. We now know about viruses, and have some ways of treating them directly, but are able to prevent infection and illness by vaccination, one of sciences wonders of the world.

But what are the similarities and what are its hints for the future?

After the third and fourth wave of Spanish flu it disappeared from the headlines, but its descendants have become what we now term seasonal flu with death rates varying from year to year. Occasional variants arise causing more serious pandemics, and the evolution of vaccination which so far has made seasonal flu more manageable tries, with varying success, to keep up with viral evolution. Flu is unlikely to ever go away and future pandemics are likely due to new strains emerging from the potent combination of compromised habitats for wildlife and spillover from bat (C19) or wildfowl (Flu) reservoirs, industrial scale animal, particularly chicken and pig husbandry and international travel.

In other words, not so different from our relationship with Sars-Cov2.

Living with COVID

So Sars-Cov2 is here to stay. Even if we killed every last viral particle in every human on the planet, it would be likely to spillover again from its animal hosts sometime soon, perhaps with randomly tweaked genes which could start infecting and spreading amongst humans all over again.

The only pandemic illness we have managed to eradicate is Smallpox, and that was because it is a human disease with no animal reservoirs. We seem sadly unable to get there with Polio. The relatively rare SARS, back in 2003, was snuffed out due to its immediacy, its severity, and some heroic work in terms of treatment and its isolation. However, it remains in existence in horseshoe bats in some cave, somewhere, so its re-emergence is not impossible.

In other words, global eradication of SarsCov2 is not possible. Living with it at the least means adding a coronavirus vaccine to seasonal flu for vulnerable sectors of our population, keeping a beady eye out for evolving mutations – which remember, might be less or more virulent – and take reasonable measures when there are flare ups – what some commentators are calling ‘respiratory hygiene’.

Keeping our own immune systems in good order will help. To achieve this we need to live lives less divorced from what our bodies and minds are designed for, prehabilitation is for life. But social and health inequalities have been driven up by the pandemic and there seems no real political will to address this most structural of issues.

Technology too will help of course. Testing, both of individuals and of the genome of the dominant and emerging variants will try to keep one step behind the virus – two steps behind will be too far. Better treatments might emerge, vaccines will improve and might control future pandemics and modern medicine will provide support for the rich populations and perhaps the poor.

We know what to do. Maintain low levels of infection and have strong public health teams ready to go. A beefed up, Finding, Testing, Tracing scheme with prompt isolation including accommodation for those who can’t isolate at home, and financial support provided at a level of the income lost. We in the UK have been at the forefront of getting this wrong and truly Victorian political thinking has been rescued by on the ball science.

The routes to prevention are also more clear – reducing international travel from its present unsustainable levels is a nettle waiting to be grasped, though may well not be. International co-operation has improved but Western nations still put themselves first. Farming systems are being developed which respect biology and the environment, and even encourage some recovery in soils and ecosystems.

Understanding bat ecology and allowing our remaining wildlife the habitats they need to live without too much of an overlap with ourselves can reduce the risk of spillover of the millions of unknown viruses they live with. Our cherished and often illusory freedoms will have to be balanced by new and very real responsibilities.

Living with SArsCov2 could improve our society, or will we just go back to the way things were before close our eyes to the reality of the times?

Finally…

I seem to end many of these posts in the same sort of way. A feeling that lessons need to be learned because the pandemic experience is so full of them. All the other big current experiences facing humanity, climate change at their apex, are full of ‘lessons’ and they are all teaching us the same thing. Unless, as a species we start to do things very differently and quickly, then everything will change around us and change in ways so fundamental that we have no way of anticipating or even imagining them.

Influenza has changed the history of the world, and now we will see how the COVID pandemic plays out with time. Whatever happens as the pandemic settles we will have to realise that how we live in the world has just got a whole lot more complicated.

The coronavirus pandemic contains many lessons but ultimately it isn’t a message, or a warning, it is a consequence.

I would like to pick holes in this, but I cannot. My perspective is always sociological and that means looking at it from similar ways you do: inequalities in health and social inequalities are joined at the hip and without enlightened health and social policy seem to be destined to be with us. Sunak’s latest offer is no more useful for social cohesion than hope is for contraception. Why? Ideology. The 1% pay offer is only understandable if you consider that his social class really don’t care, that they will always place their vision of the economy over and above human well being. Amply demonstrated, I think, in their approach to covid.

HI Benny, just tidying the blog and I saw this comment was rudely unanswered – apologies for that. Totally agree with your comments, it seems to me that with COVID (and climate) gross inequalities are not only morally abject, but also unaffordable. I hope this finds you well