The best current information is that between 5-80% (quite a range isn’t it!) of people infected with COVID19 don’t have any symptoms at all. This is a reflection of the fog caused by masses of low quality data. Indeed, we won’t know the how many infections are asymptomatic until better studies looking at antibodies to COVID in bigger population groups are done.

As doctor and and a patient, I had always felt that the more we know about problems likely to affect us, the more we are able to deal with them when they come along. So perhaps it’s a good thing to know:

“What is it like to have COVID?”

I will certainly share my own experience if and when it comes along, but for the moment, I assume myself to be COVID naive, my immune system having no idea about the imminent visitor and its effects.

This post and subsequent posts offers whoever out there who has had a COVID infection the chance to get in touch and share their experiences. Perhaps second hand experiences will help us get a feel for this a novel virus, with its surprising and odd clinical features.

Anonymity, of course, will be assured.

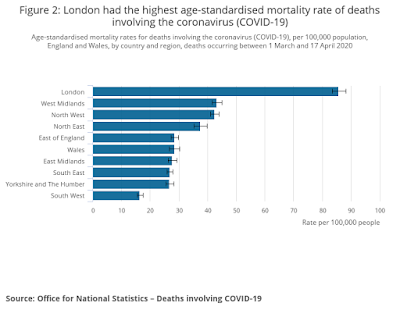

The first report comes from London, hit hardest be COVID in the UK so far. The data from ONS also shows the South West to be relatively spared. This is likely to change when the lockdown is released, thats another story. Complacency however, is not a good idea.

Tale from the front line:

(With thanks to Prof Giovanonni, whose colleague shared his experience)

COVID 19: a personal experience not to be forgotten

I am a fit 61-year-old white male, with no comorbidities. I have been an NHS consultant for 24 years, with dual accreditation in acute medicine and my core speciality.

As the Coronavirus pandemic evolved, and although I had not practised acute general medicine for 10 years, I felt that my training and experience would be of clear value for frontline care delivery. I am not an NHS zealot, but I do strongly believe in its basic principles and have been grateful for the unusual privilege of having a secure, protected and well-paid career. I felt intrinsically that I had not only a clear duty of care but also had been given a clear opportunity to be of help in this crisis and to ‘payback’ in a small way.

The preparation period was intense, with rapid closure of our entire speciality services, vetting and triaging all referrals in the system for months ahead, calling many patients to explain the reasons for cancellation of two-week wait procedures, and doing telephone virtual outpatient clinics as far ahead as possible.

In addition, there was a vast amount of new information to learn, with extensive on-line training about COVID 19, the clinical presentation of this weird novel virus, blood patterns, radiological changes, and progressive levels of respiratory support together with training sessions in CPAP. There was no doubt that both the nursing and the speciality medical staff were anxious and even scared, unsure about expectations, being deployed beyond their training and experience, and with the ever-present personal threat.

When I graduated the AIDS pandemic was evolving: however, it was much easier to deal with medically as the personal risk of infection from patients was so low. In contrast, this felt very much like preparing for battle with a real and tangible threat.

There were also evolving areas of concern. Communication with centralised NHS bodies, especially PHE, with CCG’s, and with the Trust management illustrated a massive disconnect between the drastic dissolution of our services, the measures and the rapid clinical decisions we were taking every day and the slow, stodgy, rules- bound response from the non-clinical bodies at all levels. The inability of the NHS management to think out of the box, to make quick decisions, to break rigid restrictive rules designed only for delay and procrastination was cruelly exposed. In contrast, our national speciality body, led by practising clinicians, was exemplary in providing rapid clear guidance.

Given our dual training, my team of specialists was deployed to cover the COVID 19 acute take, our speciality ward, and two pure COVID wards. I led six ward rounds -in full PPE- on the COVID wards. It was impossible not to admire the commitment of the junior doctors, the nurses and the allied medical professionals working in bizarre and extreme circumstances, and trying so hard to provide compassion and care to extremely sick, lonely patients.

Ours is an old hospital, and the lack of ventilation on the wards together with the hot PPE did give a sensation of working in a murky COVID fog. I attempted to avoid a machine ward round of just looking at the NEWS chart and tried to talk to each patient, to explain, and to teach the junior doctors, starting in the donning area with discussions of COVID, explanation of bloods, interpretation of results and then teaching more during the rounds on COVID and non-COVID aspects.

Five days after my first ward round I developed classic symptoms of COVID, and so began the frustration of organisational inefficiency compounded by deteriorating health.

The Trust testing system was run by a non-clinical department and was designed with no regard for the anxiety or deteriorating health of the ill staff member, no ability to reliably speak directly to anybody organising the testing, no reassurance that anyone would ever get back to you, no recognition that many staff members did not drive, and the placement of the local testing centre a 40-minute drive from the Trust.

Twenty-four hours after contacting the Trust team responsible for this shambolic mess, still completely in the dark as to whether I would ever be tested and with my health worsening, I considered the irony that just three weeks prior I had communicated to our Medical Director the importance of easily accessible, rapid testing for Staff members. He replied that he agreed but was constrained by PHE dictats.

As the Easter weekend was approaching, I used my seniority to bypass the Trust testing department and asked my line manager to contact the local testing centre direct. They called me within 30 minutes to say they had received no request from my Trust but reassured me that they were exceptionally quiet and had in fact received (unusually they thought) very few requests for testing from our Trust.

The lead for the testing centre contacted my Trust directly, called me back five minutes later to say that the testing request had miraculously appeared, and offered me a drive-through slot. Whilst driving, despite a high fever, to the testing centre I considered ruefully how many ill members of staff would be denied their rightful testing by organisational ineptitude, and how fortunate I was, but how unfair it also was, to be able to pull strings. There was no queue at the Testing centre. The nurse said they were hardly testing anyone.

Over the Easter weekend, my symptoms progressed. The COVID 19 symptoms are so unusual, so totally different from anything I have previously experienced, that there is a desperate need to have a clear result to at least explain what you are going through. And so began the wait. Four days later I was sicker, but still in the dark. My Trust testing department did not know where my test was sent to when it would ever be back, who would phone me with the result, or even whether it would be processed at all over Easter and was merely drying out somewhere in transit.

I was finally called, 92 hours after the test was taken to be told I was positive: my wife, desperately anxious, burst into tears that at least there was an explanation for my illness.

There was a further irony that within our Trust the Respiratory team had set up an alternative testing system to improve and enhance staff testing, but been thwarted by the Trust’s rigidity and adherence to PHE guidance. Despite being the experts, the Respiratory team were being dictated to and restrained from best practice by both non-respiratory clinicians in management leadership roles, and non-clinical management unable to relinquish their power.

Again, only through the privilege of position, was I able to access the Respiratory team’s daily ‘check-up’ phone call: the reassurance in isolation of having someone who cares call you, discuss your symptoms, and give support is immense. The denial of this invaluable service by Trust inflexibility to many of my fellow staff was an unacceptable failure of care.

(Of note -since my documentation of my experience to our Trust’s Medical Director he led major changes to the entire testing process, the organisation for this process was taken away from the non-clinical department, on-site testing for staff was started and the Respiratory clinic has obtained control).

Since graduation, I have only taken off two days for illness, and so I make the traditional worst type of patient: one who is not used to being ill. The real kicker though with COVID is the ‘double hit’ impact: you feel unusually ill initially, get teased into feeling mildly better for a couple of days, and then get struck by the real illness, the cytokine storm.

On day nine I became pyrexial again to 38, dropped my saturations to 88%, and was enveloped by a suffocating and blanketing exhaustion, apathy and myalgia. I felt frighteningly unwell, but worryingly I did not want to go back to the hospital -not through any lack of trust in the care but, it seemed like returning an injured combatant back to where the actual trauma occurred and I was desperate to avoid going back onto the COVID wards. I used instead proning (lying on my stomach) and deep breathing to get my saturations back above 92 %.

I had hoped that with the resolution of the cytokine storm recovery would beckon. However, this was not the case. By day 13 I spiked a temperature again, was short of breath talking on the phone, and noticed my pulse rate went up to 130 whilst making a slow 30-yard flat walk in my back garden.

Through the intervention of the Respiratory team, I went into the hospital, and underwent a battery of tests. Although my CRP was (still) raised at 60, by this point there were just mild pneumonic changes on chest X-ray. The negative tests (for heart failure and pulmonary embolic disease) did provide reassurance, especially given my anxiety about post-viral myocarditis. I went back home on antibiotics, and by day 16 finally felt less virus and more human.

But what about the psychological impact of this exceptional virus? An illness which is severe, but requires isolation as a mainstay of care is counter-intuitive to all medical and human impulses. The inability to touch denies a basic comfort and is an especially cruel part of this disease. My wife and daughters provided vital ongoing and critical support. Whilst I slept in a separate room, and used separate facilities, we shared the same living space and could have some limited contact: just the squeeze of a hand provides solace. Their care highlighted the essence of the value of family.

The severity of the illness undermines your confidence and highlights vulnerability to factors completely out of one’s control. I have always loved my career and chosen speciality: I have been left though with a peculiar apathy and ennui about issues I was so passionate about before. I do not relish returning to work next week.

I must confess to also being somewhat scared about the return to the Petri dish of the COVID wards. I am anxious about bringing back an infection to my wife and daughters. This illness is not suffered alone by the patient. Your family is as traumatised, and from what they experienced watching you suffer deserve to be given antibody testing as soon as available to minimise the impact of the unknown beast at the front door, brought into what is normally a place of sanctuary, by a partner just doing their job.

I admire this article for well-researched content and excellent wording. Thank you for providing such a unique information here. Find Non-clinical Jobs Texas